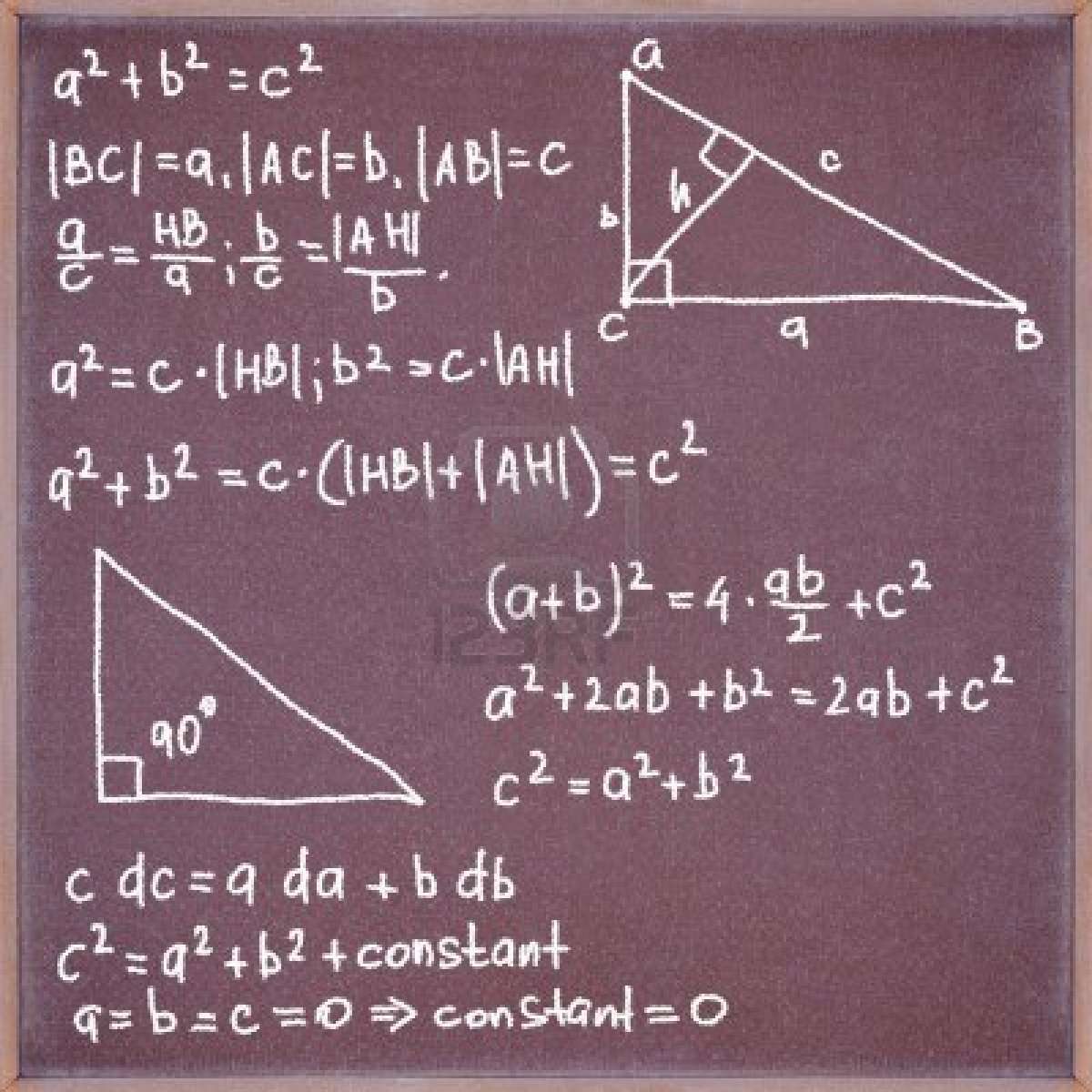

There was a chalkboard at the top of the stairs from the basement. After we shucked off our work boots, hung up our farm coats and tramped up the stairs to open the door, there it was. Our father used it to post logic problems or puzzles for us to think about and attempt to solve.

There was a chalkboard at the top of the stairs from the basement. After we shucked off our work boots, hung up our farm coats and tramped up the stairs to open the door, there it was. Our father used it to post logic problems or puzzles for us to think about and attempt to solve.

At breakfast, at least once a week or more, he queried us on new vocabulary words often from the Reader's Digest "Word Power" section, asking us if we knew what they meant. "Use them," he said, "and they will be yours."

But it wasn't just logic problems and vocabulary that interested him. He recited poetry and loved to work with us kids whenever we had memorization homework to do—a weekly occurrence for all three of us. We were impressed he could recite "Casey at the Bat" in its entirety, just as easily as he could numerous hymns, Bible verses and "The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere." He often amused us with quips from a familiar sonnet he thought fitting for a particular occasion, e.g., on April 18th he often greeted us at breakfast with, "Twas the eighteenth of April in '75 and hardly a man is yet alive who remembers that famous day and year, when one if by land and two if by sea ..."

When we went somewhere in the car together, he taught us songs by singing one line and having us repeat it. In this way we learned popular favorites, old time country tunes, Ozark folk songs and many others. My father wasn't a teacher. He never earned a college degree, but he loved to learn. These were just a few of the strategies by which he encouraged learning in all three of his children, but they certainly weren't the only ones.

Modeling from Mom

Our mother didn't go to college either, but she was just as dedicated to learning. She used a somewhat different approach, but her desire to become proficient at new skills was equally obvious. I recall the summer she decided to master every sponge cake variation in her Betty Crocker Cookbook until she had perfected them. She used the same methodology with cream puffs and jelly rolls and we were the lucky testers for her concoctions. The same sort of "make-it-until-you-master-it" approach was evident in her skills as a seamstress, her work as a bookkeeper and her approach to gardening. She mastered the art of creating an attractive suit from a Vogue pattern, upholstering slipcovers for our living room furniture, and constructing a canvas tent for a camper my father built to take us on a family vacation to Washington D.C.

My point here is to say that my sister, brother and I have become life-long-learners because our father and mother loved to learn new things. I don't recall anything they decided they couldn't do. Rather, I remember them being excited to solve a problem, to figure out a solution, to learn something new. Their attitude and work ethic inspired us all.

IQ, ACT or GPA

So how important is that attitude to helping a child succeed? Critical, according to Jeff Nelson, CEO of OneGoal, an innovative college persistence program in Chicago working to make college graduation possible for all students. According to Nelson, "Noncognitive skills like resilience and resourcefulness and grit are highly predictive of success in college" (p. 168). ACT scores, he believes, are not. According How Children Succeed, ". . . ACT scores revealed very little about whether or not a student would graduate from college. The far better predictor of college completion was a student's high-school GPA" (p. 154). In other words, it's not the IQ or ACT score that is predictive, but rather the evidence of one's hard work and determination as demonstrated by a Grade Point Average (GPA), that is the best predictor of college success.

Today's parents are often concerned about their child's education. They worry about the right preschool. They stress over enrolling their children in appropriate activities. They sacrifice time and money to ensure their offspring are exposed to the kinds of experiences they believe will help them to become successful, well-rounded adults. They may even put too much emphasis on test scores and getting into the right college or university. If we want our children to succeed, however, we might want to consider how important it is that we, ourselves, model an enjoyment of learning new things. Are we avid readers? Do we relish new experiences where we learn more about other people or the world about us? Are we interested in learning new skills? Do we involve our kids in activities where they can learn with us? How likely is it that our child will be interested in creating something, learning a new skill, or mastering a talent if we fail to demonstrate the same sort of enthusiasm?

The good news is that no matter how old you are, you can still learn new things. An even more exciting prospect is that while you're doing it, you can inspire a young learner to learn with you. Plan now to learn something new this week and share the experience with a child.